Happy Birthday To Me

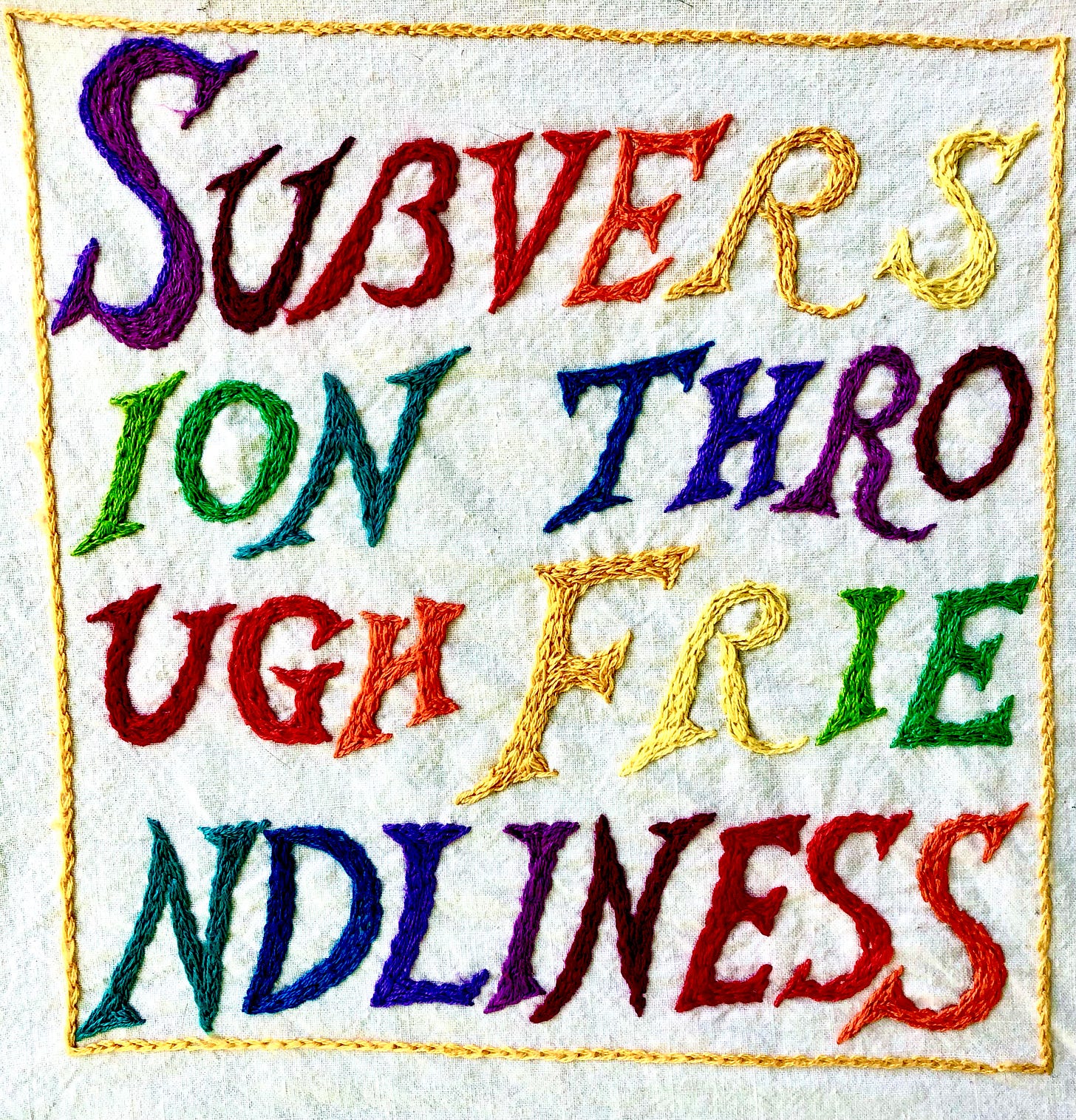

fun fact: the below image was embroidered for me as gift by Ursula K. LeGuin, a longtime fan of the motto. Design by Erin Brand for chorus propaganda.

Welcome to Subversion Through Friendliness, a digital zine.

Substack is a platform for artists like me to share ad-free content, and give people easy opportunities to provide us with readership and financial support in small monthly or single large donation amounts. On the advice of my friend and peer mentor, artist, family steward, and deep thinker Carson Ellis, I’m joining the fray. July 16th is my birthday; launching Subversion Through Friendliness is my birthday present. As a person on my email list, I think you are automatically subscribed, and you will get updates in email form when I post them. You can read some of my posts for free, and some will cost. I don’t quite have the hang of things yet, I don’t understand how this all works, but I’m looking forward to trying something new. I’m leaping in!

Today I’m offering a short description of your weekly read, little essay about the phrase ‘Subversion Through Friendliness,’ and a story for paid subscribers. Does the paywall work? I have no idea!

Things you will read about: Revelations, rants, & reactions to events in the world, personal writing, culture reports/Gen X vibes, breast cancer fallout, menopause, aging, moon and other witchy reports, book, zine, film, tv, music reviews, reports from the day job as a warehouse worker, grief, obituaries, cats, updates on It Did Happen Here: An Antifascist People’s History, the book I helped write and edit that came out this May, zines I publish, and commentary on these wild times. Fisher poetry is doubtless unavoidable, as are random drawings of animals promoting events.

Will I do a daily post? Maybe! Good Night People of Earth was a great project and I’ve missed it. I’ve been writing most recently on Instagram, posting to Facebook, and my recent participation in that addiction has felt like I am in some advanced stage of cultural heart disease. All I want to do is make art, while the brutal inflation of the economy tremendously impacts our little family. If giving birthday presents makes you happy, if you want to support art and writing, why not sign up for $5 for a month and see how you like it? Tell a friend, forward this to someone who might appreciate how this helps us move through our shared experience.

Here’s my first post.

SUBVERSION THROUGH FRIENDLINESS

I am a fan of a good motto. Bike mechanics in my college town introduced me to the concept in the late 80s. An early one was ‘Accelerate THROUGH Danger,’ a variation on ‘they who hesitate are lost,’ a directive on how to survive a potential bike wreck. I soon adopted the practice of the short phrase as navigation tool. When I quit drinking at age 23, instead of boiling in a shame bath for having participated for years in an unsuccessful coping strategy, I took a page from the mechanics’ grease-stained social handbook and turned the phrase ‘Moderation Through Excess’ as a way to both describe and forgive my coming of age.

I was raised in a household that believed in education, especially as a tool for succeeding in capitalism. My sisters and I amassed skills early, playing instruments, joining civic clubs, volunteering at St Mary’s church, all in service to creating a profile worthy of a scholarship award at a university whose pedigree could increase the general worth of the family. A stint as a foreign exchange student looks good on a college application, so at 16 my family sent me to the tiny village in southern Germany that my mom’s parents left behind in 1928. Massenbachhausen had around 3,000 inhabitants in 1983, about half the size of my home town. The first phrases I learned in my ancestral dialect of Schwäbisch were Good morning! Good evening!

All the villagers, without exception, greeted everyone else as we passed each other on the sidewalks. Grouchy old men, prim matrons, slutty teens, hard-working middle-aged parents, toddlers, my cousins, our immigrant friends from Italy and Turkey,—everyone said hello. My grandparents had caused a scandal as young people when they fell in love across strict class lines. My Oma married ‘down,’ and ran off to America in pursuit of romantic love and a life of unimagined drudgery as a farmer. As a result, through my mother’s side I am related to almost everyone in Massenbachhausen. If I snubbed someone in the street, my host cousin would surely hear about it and ask why I hadn’t greeted Frau Gantner or Herr Muth, didn’t I know that was my mother’s father’s brother’s second cousin? How could you ignore your cousin’s Tante like that?

I returned after six months, horizons broadened, fluent in a second language, and pondered this cultural difference. What would it be like to live as if everyone were a cousin of some kind? As humans, weren’t we? I began greeting people on the streets of my small, racist, anti-Semitic, culturally conservative town as I had done in Massenbachhausen, where it was seen as one more thing I did that was different than everyone else. I did it when I went away to college in the Midwest, where people around me thought it was some sort of small town thing. I moved into Chicago and continued, despite the scorn of my friends, who came from suburbs and aggressively cultivated big city cool. I connected with activists, artists, anarchists, and as I differentiated myself outwardly with weird clothes and colorful hair, fraternized with tattooed, pierced, companions who sported spiky jewelry, I leaned even harder into connecting with strangers—and this is when it clicked for me.

To look at every person I passed and say ‘hello,’ to say, ’I’m here with you in this moment and we are both humans,’ felt like I was undermining an unspoken expectation that someone like me could not possibly know someone like you. To say hello seemed the tiniest but still deeply significant act of connection I could perform. This was long before the ‘Practice random acts of kindness’ Princess Diana bumper sticker became ubiquitous. Sometimes my one-person crusade for friendliness felt futile, but then a truck full of Black laborers working on a snowy day in my neighborhood would all wave and shout hello, recognizing me as the weird kid who said hi to everyone, and my instinct that I was onto something meaningful would be renewed.

A decade after meeting the mechanics in my college town, I was in Portland, Oregon, organizing with the Amalgamated Everlasting Union Chorus. We were initially a one-event concept band that morphed into a queer and queer-friendly protest chorus with room for parents, children, and other unlikely activists. We spent almost ten years in the streets of Portland, singing songs of hope, resistance, and cultural critique. I can’t remember when the phrase was born, but Subversion Through Friendliness was quickly adopted by the chorus, and we developed the philosophy through the many protests of the Clinton and Bush years. We eschewed the usual activist uniform— t-shirt for a good cause or righteous band, kaffiyeh, Birkenstocks for hippies, or the classic all black—in favor of pirate drag, tutus, prom dresses. Don’t get me wrong, we were still young know it alls who wanted to berate society into addressing injustice just like our grim comrades, but in a way that said ‘Join us because we are working to be on the right side of history and we are also more fun than the fascists.’

Subversion Through Friendliness, to me, is about fighting disconnection bred by fascism in all its forms. I imagine a reader thinking, at this point—like all my old comrades, college chums, and fellow small town citizens—that I am preaching some sort of ‘live laugh love’ garbage, how could this be subversive?

If it were that meaningless, I argue, it would not feel so much like pushing against a vast tide of learned and cultivated indifference. If it were not subversive, people would not work so hard to avoid doing it.

Subversion Through Friendliness is not about making friends with people; it’s mutually acknowledging our humanity as we pass, as we did in the village where everyone was my cousin. It can feel awful to push against the armor we all don when we go out in the street. Just ask my friends, who for years have listened to me gripe at how aggressively people pretend I did not say hello to them.

I still say my quiet hellos to people on the street. I keep my hands to myself. I do not wave. I talk to passers by from my porch. I notice how hard people work to avoid eye contact, to pretend I am not walking by them, even as their dogs or children greet me. I see parents and caregivers teaching children, by example, to avoid people.

I understand that our society is in crisis. The recent acute pandemic and ongoing plague risk has required us to separate and distance ourselves for very real health reasons. I understand how it might not feel safe to offer even the tiniest connection of hello, carried forward on a wave of breath. I also understand that on Earth, connection is the key to our survival, and that capitalism drives disconnection. There is a deep investment in white supremacy teaching us to see each other as Other, as potential threat, as not-the-same-kind, essentially as I am human and you are not quite. How do we find a way through?

Sometimes I look around Portland and imagine no roads, no telephone poles, no city as we know it, just paths through a forest. If I walked in this valley 300 years ago, would I pass by another human without acknowledgment? Would I hide from other humans out of fear that they would kill me, take my stuff? Would I wave, offer water and food, a smile? Is there a place in between where we can imagine a reality from which to navigate these coming years of accumulated climate chaos?

Friendliness is not stupidity. It is not creepiness. It is not grasping. It is the first step to kindness. It is rooted in curious solidarity. It is softly fearless.

For now, hello.

Paid subscribers, what follows is an autobiographical story of my childhood, inspired by a prompt in Lynda Barry’s book What It Is: family car.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Subversion Through Friendliness to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.