In a few days I leave for Enterprise, Oregon to give a talk about two fierce rabble rousers from Oregon’s labor history at the invitation of a writerly outfit called Fishtrap, in celebration of The Big Read. Fishtrap is an organization that since 1988 has provided Western writers a place to come together and share work in Wallowa County, beyond the I-5 cultural corridor stretching from Portland to Ashland; since the late 80s the organization has continued to add quality literary programming for Oregon’s westernmost residents.

Seventeen years ago Oregon Public Broadcasting sent a film crew from Oregon Art Beat to the eleventh FisherPoets Gathering, where I met then-producer Mike Midlo, who recruited me to show his crew around town. In return, they favorably spotlighted me throughout the resulting episode. Mike moved in 2013 to Wallowa County where he got involved with Fishtrap, and ever since has been hallooing at me, over the mountains and down the gorge, trying to fit me into the landscape in a professional way, and he finally nailed with The Big Read.

The Big Read is an annual event supported by the beleaguered National Endowment for the Arts, and supports its longstanding efforts to get art programs into communities around the country, with the radical idea that maybe if we put a book into someone’s hands instead of a gun, we can have a better outcome (my mission statement, not theirs.)

“The NEA Big Read annually presents a selection of novels, poetry collections, short story collections, memoirs, and/or books of essays that inspire conversation and creative responses. Funding is then provided to nonprofit organizations around the country to host dynamic community-wide reading programs designed around one of these books and in collaboration with local partners to develop and conduct engaging events and activities. Organizations apply for funding through a grants program managed by Arts Midwest. Each community program that receives an NEA Big Read grant – which ranges between $5,000 and $20,000 – is also provided with resources to help them succeed. These include outreach materials and tools to help grantees develop public relations strategies, work with local partners, and lead meaningful book discussions.”

—NEA website

This year’s theme is ‘Where We Live,’ an idea neutral enough for a bipartisan-funded arts organization; I imagine executive and programming directors winnowing a list that can include ALL ‘Mericans, since the NEA must answer to the scrutiny of politicians in a way we can only dream would apply to the Department of Defense. “What about ‘Where we Live?” these harried English MFA and PhD. holders ask as they brainstorm in my imagination, “Everyone has to live, right? Everyone has a story about where they live; we can’t get any more inclusive than mere existence!”

Fishtrap is one of 62 nonprofits awarded grants for this version of the Big Read. Participants select a book of literature from the Big Read Library, a list of fifty titles that includes classics from as far back and unobjectionable as Jack London’s The Call of the Wild, White Fang and Other Stories or Thornton Wilder’s Our Town, and as complicated and bracing as Claudia Rankine’s Citizen: An American Lyric.

Mike and the folks at Fishtrap selected Jess Walter’s 2020 novel The Cold Millions. I’m happy for Mr. Walter to receive some in-person due for the story; its pandemic release resulted in no doubt many a tepid zoom presentation. He’s a good writer, rooted in years of journalism working in his hometown of Spokane, Washington, where The Cold Millions takes place. His first book, Every Knee Shall Bow: The Truth and Tragedy Of The Randy Weaver Family (re-released as Ruby Ridge) was a 1992 finalist for the Pulitzer Prize. I’m sorry to miss his visit to Fishtrap, and grateful that the organization could accommodate my midweek scheduling requirements.

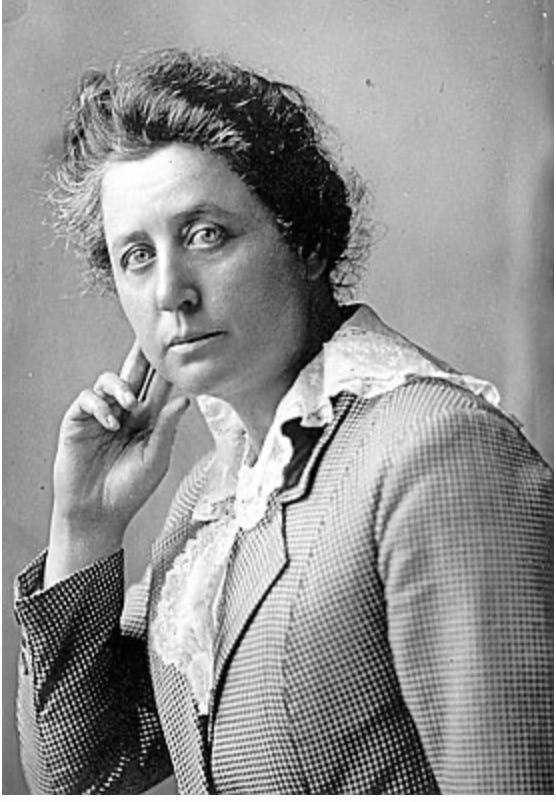

The Cold Millions centers on the Spokane free speech fights of 1909, when over 400 men associated with the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW, aka the Wobblies) were beaten and stuffed into local jails, where they were mistreated, mischaracterized, and starved. Walters introduces us to various Western characters common to the days when industrialists aggressively ‘expanded’—colonized—the West, and the robber barons in charge of mines, mills, and railroads chewed through human beings with a calculated, profit-hungry detachment similar to the deployment of incarcerated men fighting fires that eat through Los Angeles as I write this. The novel focuses on two homeless men, a teenager and his slightly older brother, as they struggle to find a place for themselves after the death of their parents. The IWW features heavily in the story, along with the notorious and talented young speaker Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, the only woman ever to go out on the IWW orating circuit. The Cold Millions cleaves closely to history, as befits the work of a journalist, and exposes many ugly truths that again, are reflected in recent news horrors. I appreciate that more people will learn about the IWW and its Free Speech Fights which peppered the West and helped bring about the eight-hour day. 1909 was the year the IWW began publishing the Industrial Worker in Spokane, which identified the boomtown as a prime target of struggle between wealthy tycoons, itinerant laborers struggling to survive, union organizers engaged in organizing working people with the reminder that there are more workers than bosses, and residents who just want things to be normal, as well as opportunists, entertainers, cops, grifters, and Pinkerton thugs. It’s a good book, grounded in facts and shaped with compassion and a cold hard look at reality. I hope you read it.

My talk, titled Unabashed, Unafraid, Unashamed: Women Fighters on the Front Lines of Oregon’s Labor Movement, looks at the lives of two veteran supporters of workers: Dr. Marie Equi and journalist and union organizer Julia Ruuttila. You can join us at 107 West Main Street or tune in 7pm Wednesday January 16 at fishtrap.org, or wait until next week when I’ll publish some sort of written version. I plan to record and transcribe it but unlike Mike and his long ago film crew, I have to produce my own events and I can only pray to remember and leave post it notes everywhere in the hope that I press record in those last nervous minutes before I share the history of a hotheaded lesbian abortionist and a furious scribbler with the good people of Enterprise.

In advance, let me acknowledge that the description I sent to Mike was so poorly worded that he inferred that Julia Ruuttila and Dr. Equi were lovers. My bad. While Dr Equi had several great romances, Ms. Ruuttila was not one of them, being 35 years her junior and a lover of men, though they did meet several times. By the time I caught the error and tried to rectify it all the press releases were out. “Too late,” Mike said, “Blame it on Fishtrap.”

In Marie Equi’s day—she practiced medicine from 1905-1930—the business of doctoring had yet to be dominated by shareholders profiting off the sick and dying, so she spent her days treating patients in her practice and taking care of Wobblies for free, rather than struggling to limit time with patients so that hospitals could make more and more money. What would she think of the biggest strike in Oregon history kicking off in the middle of winter? At 6 am January 10, around 5,000 Oregon healthcare workers walked off the job at over eight hospitals across Oregon, after months of frustrating roadblocks from Providence Hospital bosses at the negotiating table.

“We’re asking for competitive compensation that reflects the reality of our work, the long hours, the emotional toll and the ever-growing demands that are placed on us. We’re asking for wages that keep pace with inflation.”

—Gina Ottinger, RN, to the Oregon Capital Chronicle, January 10, 2025

As a lowly hospital grunt, I wonder how this will ripple through our flu et cetera season. I’m proud of the healthcare workers, and also sorrow for them, for their patients, for the families that will be dragged through this, for workers arriving again at this fierce and miserable crossroads that includes thousands of people trying to get care in the middle of flu season, while COVID haunts us, under a looming terror of the H5N1 bird flu, the HMPV virus that’s been known to infect humans since 2001 but you will read about in the news as the ‘new virus from China,’ as well as various ailments that accompany everyday life at the unsustainable stress levels ordinary life now entails.

In a recent statement explaining the strike, ONA said: "Providence is a $30 billion corporation whose top executives make million-dollar salaries and are too focused on profits and not enough on high-quality patient care. Providence's outgoing CEO made more than $12 million in 2024."

—as reported by Brett Wilkins, Common Dreams January 10, 2025

The hospital where I work is not on strike, though nurses at varying sites in our system are organizing, and I have seen statements of solidarity and support for Providence clinicians expressed on social media. Oregon is a ‘right to work’ state, which means that labor unions are prohibited from entering contracts with employers—previously terms like ‘open shop’ were used to describe a workplace where each employee decided whether or not to participate in union organizing. The Orwellian language is confusing; basically it is rooted in the idea that an employee does not have to go on strike—has a right to work—rather than cleave to the union’s actions. Union organizers charge that employees in departments like mine benefit from collective bargaining without contributing anything. Supporters of ‘right to work’ say that they just want to go to work, they don’t want to have to pay dues or involve themselves in politics. Or at least, that’s what a lot of people at this hospital say. Supply departments in other hospitals are unionized; no one at my department is interested, even though one guy works a full time second job at a school district where he is in the janitor’s union. One of the phlebotomists told me that as a part-time worker he does not want to give his money to a union that would not benefit him to the degree that it costs him in time and money.

As someone who has read a lot about unions, and is headed east next week to give a talk on individuals engaged in labor activism, it’s embarrassing to me that I’ve never been in any union other than one year that I paid dues to the IWW as a kind of pathetic gesture of faith. I envy and admire friends in the strong union cities of Minneapolis, Chicago, Milwaukee, who belong to and organize with their unions. I want to transfer into one of the closed shops, which unsurprisingly are in the city rather than the burbs. But for now, I’m here.

One of my co-workers was employed briefly at one of the Providence hospitals, and described the place as consistently at capacity—over 400 patients—despite being in ‘non-emergency’ status. The nurses have been struggling to get management to deal fairly with them in good faith bargaining for several years. As I understand it, unions make more money for everyone in the long run, because people are loyal to jobs where we feel respected, where we feel like we have the power of a seat at the bargaining table, which unions provide. Fighting against unions seems to me to be addiction behavior, the way Providence, Trader Joe’s, Amazon and so many other knee jerk oligarch reactionaries reach for antiunion antics as if shitting on your workforce is the only solution, almost like it is an identity. To be anti-worker is to be a boss, and you want to be a boss, doncha? This is as stupid as blocking high speed rail in favor of continuing to rely on fossil fuels which in turn relies on continuing genocides across the globe. Makes no sense, and yet here we are.

There’s not much news on the national level of this massive strike, given the spectacular and terrible livestream of the horrific fires in our nation’s second largest city, home to an incredibly diverse and thriving neighborhoods beyond the movie business. My heart goes out to the people of L.A., the historic rich cultural home to so many, including the largest settlement of Armenians outside of their ancestral homeland.

Some good news, if you read last week’s post: I’ve been texting for two weeks with a newly homeless person, trying to connect them with resources. I organized a meeting between some young people in the group house down the street (‘we’re almost thirty Moe, we’re old, I hear them say in my head) and the reluctant urban camper, during which the house agreed to provide a charging station, dry storage for gear and a secure place to lock the e-bike, as well as a separate entrance to a porch with a sweet little loveseat out of the weather. It’s been wild, reading The Cold Millions while trying to help someone in modern times access basic needs; I appreciate that the spirits of Julia Ruuttila and Dr. Equi fortified me. It feels rotten to not be able to do anything, which is, in a way, a privileged position. Like, if I can’t fix things with a phone call or my puny bank account, then I want to give up. Instead I kept trying and texting, and reading about Dr. Equi getting thrown in San Quentin for speaking out against war, or Ms. Ruuttila getting her ankle broken and beat up for confronting a man she thought was a scab, and I keep trying, and text some more. At the meeting, I was moved to hear my new acquaintance say that texting with me, and being able to talk on the phone to a friend in another state kept them going every day.

I wish for you all shelter from the worst actions and weathers, a capacity to keep your minds open, the guts to fight for what is right over what is safe, and may the spirits of our righteous and mighty dead help keep the flames where they belong, in our hearts.

til next week.

Beautiful Moe! I wish I could be at fish trap. I’ll have to make it out there sometime