Last week we sent off the last of our fisherpoet houseguests, one to Kodiak, the other to the coast, after the standing room only Ebb Tide FisherPoets in PDX event Monday February 24 at the AFL-CIO union hall. The camera on my phone is broken, and by the fifth day of the annual gathering of poets, my brain was too cooked to remember to ask people to take photos. The low ceilings and bad lighting would have made it a tough ask anyway, so I’ll just let you imagine. Kvichak River set netter Billie Delaney led a small team of folks setting up chairs in proper theater seating, to maximize sightlines and accessibility. Poets read in front of a giant mural depicting the state of Oregon bisected by a jaunty AFL-CIO banner; a sign taped to the back of the music stand read ‘WORKERS OVER BILLIONAIRES.’ It felt great to be at an event celebrating work at a union hall. The cross-pollination added a heightened sense of togetherness to the evening, though no one from the union was present. The next day—Tuesday February 26—200 union members visited Salem for the annual Oregon Labor Legislative Conference and Lobby Day, and their preparations precluded attendance at a three-hour long night of salty yarns.

Yes, three hours. Far too long! We crammed 13 poets on the bill, including a couple of last-minute offerings from local treasure Will Hornyak, whose new book This Altar of Earth And Sky has already sold through two on-demand print runs, as well as David Bean who gave us the classic: a long introduction to a short poem. After ten+ years of local FisherPoet events (Lara and I can’t remember when we started), our audience is used to the marathon, but this year really wore me out. My brain is still not recovered. We’ve decided to bring back the Flood Tide set, so next year—if there is a next year—we will host poets Wednesday February 25 in advance of the gathering, scheduled for the 27th-March 1, and Monday March 2 for the outbound tide of words. Priority is given to out of towners, and we hope to keep the event to 2 1/2 hours. As fishing people, we are acclimated to suffering, including the necessary indignities of having people walk out just as we approach the mic, but we don’t expect everyone to endure an endless flow of ocean metaphors. It’s tricky, we don’t want to leave any poets out, and we don’t want to punish our kind audience. So, like farmers and fishing people everywhere, we look to the future and say, there’s always next year!

To mention notable presentations from the gathering in Astoria: on Saturday morning, Shoshone-Bannock Yakima-Nez Perce tribal member and fisherpoet Ed Edmo, with the support of Nancy Cook, presented “Echo of the Waters: Honoring Native Traditions” to a standing-room-only crowd of about 120 people at the Columbia River Maritime Museum. Joining Ed were Indigenous fisherpoets, including Musqueam fisherman Wilfred Wilson; Unangax̂, Sugpiaq, Yup'ik and Iñupiaq setnetter Melanie Brown; and Eyak Village elder Lloyd Montgomery. Melanie played a new song, TEK (Traditional Ecological Knowledge) talking about the importance of slowing our lives to align with, learn from, and restore our relationships with the land, using TEK as our guide. Lloyd drummed us in, and also did trickster work, teasingly saying, ‘My friend Ed Elmo’ while Ed corrected him over and over, finally saying, “I’m not a furry red puppet!’ Wilfred Wilson shared a poem about his life in Coast Salish lands of Delta, British Columbia.

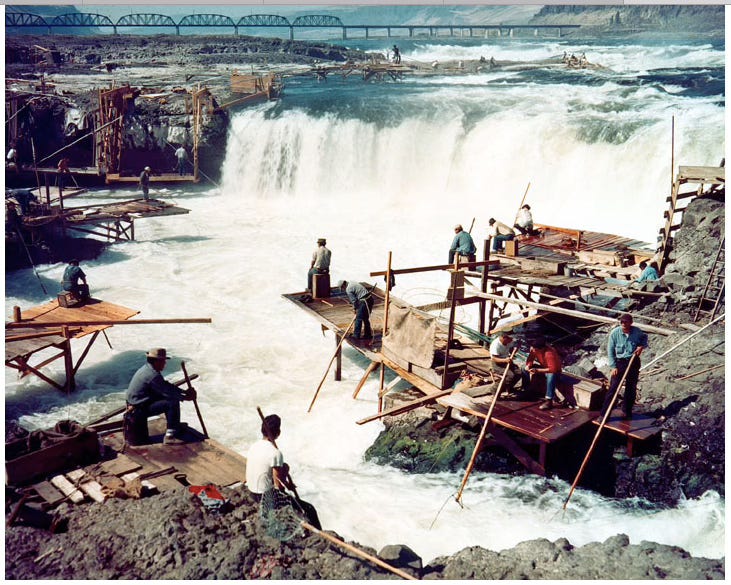

The presentation was a memorial; it featured photos and documentary film clips of the 1957 inundation of Celilo Falls by the Army Corps of Engineers in advance of the installing the Dalles Dam. We got to see a lot of images of an adorable Ed as a child, including some of him dancing at the annual Salmon Feast celebrated by the many tribes who traveled annually to Celilo Village to fish and trade. Ed told stories of his life both on film and at the podium, sharing the humiliation of being the living mascot for the local sports team—a role his father encouraged in the hopes that the assimilation would pave an easier way for Ed as the family navigated the complete destruction of their way of life.

Wy’am is the ancient name for the falls, ‘Echo of Water Falling on Rocks.’ We learned how the presence of the falls permeated everything, from the mist to the constant roaring, and the eventual silence. I’m grateful that for whatever reason the museum attendant let me in just as the event was starting—people were being turned away as early as 9 am for the 10 am presentation. It was good to hear Ed speaking out: “Everyone likes an Indian in feathers, but no one wants to hear about how many of us have died.”

“Echo of the Waters” ended with a group stroll through the Columbia River Maritime Museum’s new exhibits Cedar And Sea: The Maritime Culture of the Indigenous People of the Pacific Northwest Coast and “ntsayka ilíi ukuk: This Is Our Place.” Folks have at least 2 years to view the exhibits, which include an opportunity to greet Skakwal (Chinook Wawa word for lamprey or eel), a 24-foot canoe still in use locally. I encountered my writer friend and Ponca tribal member Cliff Taylor and his partner in the audience, so we went through together to see the exhibit. I was chatting with someone when I heard a voice rising in song, and turned to see Cliff standing before Skakwal, arms low and wide, hands open. When Cliff met the canoe, he heard it asking him to sing, he told us later. We stood in the shiver of his beautiful, impromptu song as it echoed through the building; Lloyd Montgomery accompanied him on the drum after the opening notes rang out over the canoe.

The Chinook Nation, which is made up of the five western-most Chinookan-speaking tribes at the mouth of the Columbia River, has sought federal recognition for over 120 years. In 2001 the tribe obtained recognition, but were heartbroken just 18 months later when their recognition was rescinded. When Cliff Taylor was born, the Ponca tribe to which he belongs had been “terminated”—unrecognized by the federal government—since 1965; in 1990, when Cliff was a young boy, Ponca people were again recognized, thanks to the efforts of the Ponca people and especially Fred Leroy. This restored specific benefits, capacity to hold leadership positions, and many other basic dignities inherent to Indigenous nationhood. To hear a song in a museum dedicated to a living canoe, at a time when that canoe continues to carry elders who have been fighting so long for recognition was powerful, and for me a highlight of FisherPoets. I was proud that the gathering created the container for this connection to flow naturally.

A brief overview of the Chinook Indian Nation’s claims are as follows:

Seeking a Declaratory Judgment from the Court that the Treaty of Tansey Point between the United States and the Lower Band of Chinook Indians was constructively ratified by various Acts of Congress and these Acts have resulted in de facto or constructive federal acknowledgment of the Chinook as an Indian Tribe.

Seeking an order invalidating the Bureau of Indian Affairs (“BIA”) regulation prohibiting the Chinook, as a Tribe once denied formal recognition from re-petitioning for recognition through the BIA.

Seeking a judgment acknowledging Chinook Indian Nation’s right to monies appropriated to us by Congress and awarded to us by the United States Court of Claims.

Finally, because of the BlA’s historical and continuing mismanagement and malfeasance, we are asking that a Special Master be appointed by the Court to monitor agency action or inaction in response to this Court’s orders.

As of Spring of 2021 the case is ongoing.

from chinook nation.org

One way to support Chinook Nation efforts is to sign their petition.

For decades, the FisherPoets Gathering has provided opportunities for people to share information about ocean science and health; it was at the gathering that I first learned about ocean acidification, perhaps twenty years ago, long before this looming catastrophe was on the radar of media outlets outside of ocean science and fishing industries. This year was no exception: with Brad Warren of Global Ocean Health presented on restoration projects involving algae and rocks; Graham Klag of the North Coast Watershed Association held a workshop on the efforts of the North Coast Watershed Association to mitigate impact of hatchery dams on salmon migration, and Melanie Brown, outreach director of Salmon State, gave an update on the health of the salmon rivers and fish of Bristol Bay.

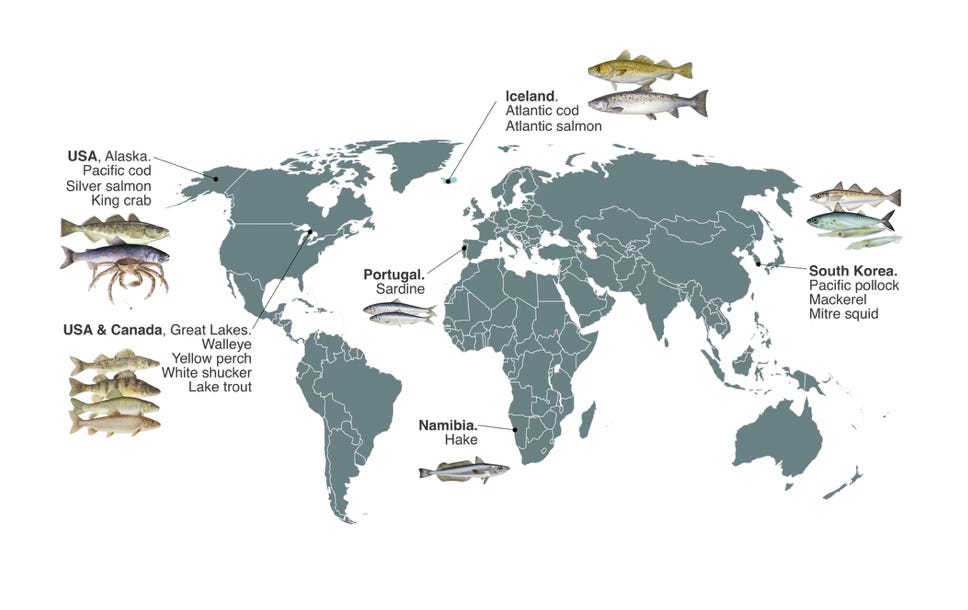

My loving man attended a talk hosted by our friend Rob Seitz, captain of the f/v South Bay and co-owner of South Bay Wild restaurant on 9th between Commercial and Marine Streets in Astoria. Joining Rob were Dr. Alexandra Leeper, CEO of Iceland Ocean Cluster, and Marcus Hinz of the Oregon Ocean Cluster . I’m going to tell you briefly what George told me, since I have to leave for work in twenty minutes and I don’t have research capacity this morning. I plan to learn and write more about this in the future.

Fishing has always been a huge part of the tiny nation of Iceland; for decades during the 20th century the country has fought to retain its rights to cod and other species. Modern fisheries depend on a (flawed) quota system to regulate fisheries, where fish are allocated, bought, sold, traded while they are still swimming around. Iceland lost heavily in what is known as the Cod Wars, especially during the formation of the European Union. The solution for fishermen has always been, ‘well let’s just fish harder, and catch more.’ More fish on the market brings the price down, which means boats have to catch even more. As George related to me, the women who were married to fishermen looked at the situation and decided to go about it a different way. (This is a HUGELY simplified view, anecdotally presented, and it’s putting the old journalism professors in my head on edge, but I promise I will learn more and relate it.) The desire for a better outcome for families, oceans and fish populations is what is behind the Iceland Ocean Cluster Initiative.

In a former fish processing plant, fishermen, scientists, and entrepreneurs across multiple industries collaborate to identify how to use 100% of a fish species instead of the traditional use of cutting out the flesh and making soup out of the bones and head. So far the industrial applications include the beauty industry, where scales add sheen to makeup products; the medical industry, especially in creating patches for burn victims out of fish skin; and evidently there is an enzyme in the stomach of a cod that does something incredible that I can’t remember, but George is sleeping so we will have to wait until I can interview Dr. Leeper and Rob at a future date. George said that the combinations of these applications take the cod from a market value price to $5,000 per fish. Now, I want to stress that George is not the exaggerator in the family, that’s me. This is an exciting collaborative opportunity that requires cooperation across borders, industries, and world views, with profound potential for promoting survival on the planet.

Between TEK and high-tech innovations, coastal fishing communities have much to offer us all. And because everything is happening at the FisherPoets Gathering, people run around all day soaking up shared skills and knowledge, and run around all night listen to stories, songs and poems. After returning from FisherPoets, in a desire to continue developing a resistance mindset, I dove back into Leanne Betasamosake Simpson’s excellent book of Indigenous theory As We Have Always Done: Indigenous Freedom Through Radical Resistance. In chapter one I reconnected with the idea of “grounded normativity,” a concept Simpson synthesized with Glenn Coulthard. As I understand it (as I begin to understand it, groping my way through out of a default settler-colonized mindset) grounded normativity, or ‘place-based solidarity’ is when we understand who we are by what we do, in the place we do it.

My loving man George is a fisherman of the Moray Firth, the North Sea and the Atlantic Ocean. When I met him, he told me, “My father is a fisherman, my father’s father was a fisherman, my father’s father’s father was a fisherman, all the way back.” George made me Cullen skink (a kind of smoked haddock chowder) and we went for a walk over the cliffs where his people had fished for 400 years. It’s how he knows who he is.

As I read Simpson’s first chapter, I realized why FisherPoets sold out this year, why we are drawn together to tell our stories, and share our lives—it’s a place where we can be in grounded normativity. We share that with anyone who manages to squeeze in to one of the seven venues or the workshops. When we engage, as Ed did, in memory activism, or in connecting people to the health of the oceans like Brad, or to the health of the rivers and the fish, like Melanie, or to the health of global fishing communities, like Rob, Marcus, and Dr. Leeper, we invite others to participate in a taste of that. People today—digitally isolated from true community—seem hungry for that.

I enjoy a rare feeling at FisherPoets, where I am most myself, where I feel safe, seen, and held, where I feel like people want what I have to give, where I connect most deeply with why I’m here on Earth. It’s not when I am on the stage, and standing in the loving holy hush where the audience and I breathe together, though that experience is nourishing and powerful. It’s when I’m tromping around the rainy streets of a fishing town with my fellow fisherwomen and queers, in our Xtra Tufs and town jeans, hoodies pulled up over our ball caps, dodging rain and laughing and catching up. It’s February, wide cheeks redden in the cold, but we don’t care. We are grounded, in motion, in our stories, alive.

Next year, February 27-March 1; PDX flood tide set Feb 25, ebb tide set March 2. Until then, I’ll give you the traditional Kodiak deckhand’s farewell: see you when I see you!

Holly! More Stories! Thank you for what you do to make that happen

Thanks, Moe!! I think you're right--we need stories more than ever right now--thanks for articulating this so beautifully--and helping keep Fisherpoets alive & thriving.